Alien (1979)

"I ain't drawing no straws, I'm for killing that goddamn thing right now.”

Parodied to the point of boredom (for example, see Kenny Everett’s take on the breakfast scene in Bloodbath At The House Of Death, or to bring it a bit more up to date, the rather brilliantly done Nik Naks ad), for the jaded palates of a 21st century audience, it would be easy to assume that Alien must have lost its power to shock.

And before we go any further, Alien is a British film - it was made here, with British money, a British director and a British cast.

When I came to review Alien, it had been a number of years since I’d seen it. I sat down, pen in hand, wondering whether it would still hold my interest - let alone scare me. After all, back in the early 80s, along with An American Werewolf In London and Jaws, Alien was part of an unholy trilogy of films that made up a rite of passage for every 11 year old boy, getting their first showings on terrestrial telly and being consigned forever to sellotape covered Betamax tapes across the country. All three scared the crap out of me and everyone else in my class at school. American Werewolf has still got “it” (whatever “it” may be) and of course Jaws still regularly appears in those “top 10 scary films” polls Channel 4 trot out every other fortnight (not bad for what was basically a kid’s film), but, I sat there wondering, can Alien cut the mustard, twenty years on?

Well, yes and no. It's a beautifully shot, brilliantly written film, but it is just not scary any more. Perhaps it's just a case of seeing it once too often - all the shocks now seem telegraphed too far in advance, and compared with a lot of films, you just don't see much (the chest-bursting scene excepted). But there is an awful lot to enjoy, and as a work of cinematic art, Alien is without peer.

There are things which do suffer when viewed by 21st century eyes. The spaceship which acts as the “haunted house” setting, Nostromo, doesn't appear half as impressive as it once did - it's basically just a load of Airfix kits stuck together. But even that is infinitely preferable to some sleek and soulless computer generated effects monstrosity.

And as the crew wake up from their hypersleep and mumble their way through breakfast, the modern viewer begins to wonder how so little action can be stretched out over such a large portion of a film. It just wouldn’t happen these days. Yet there’s something compulsive about watching it – a bit like turning on live Big Brother after coming in from the pub, although without the insufferable twattishness. There have been few films since that have dared to show how humdrum life in the future will probably be (ignoring the obvious excitement of huge scary monsters biting people's faces off, for the time being).

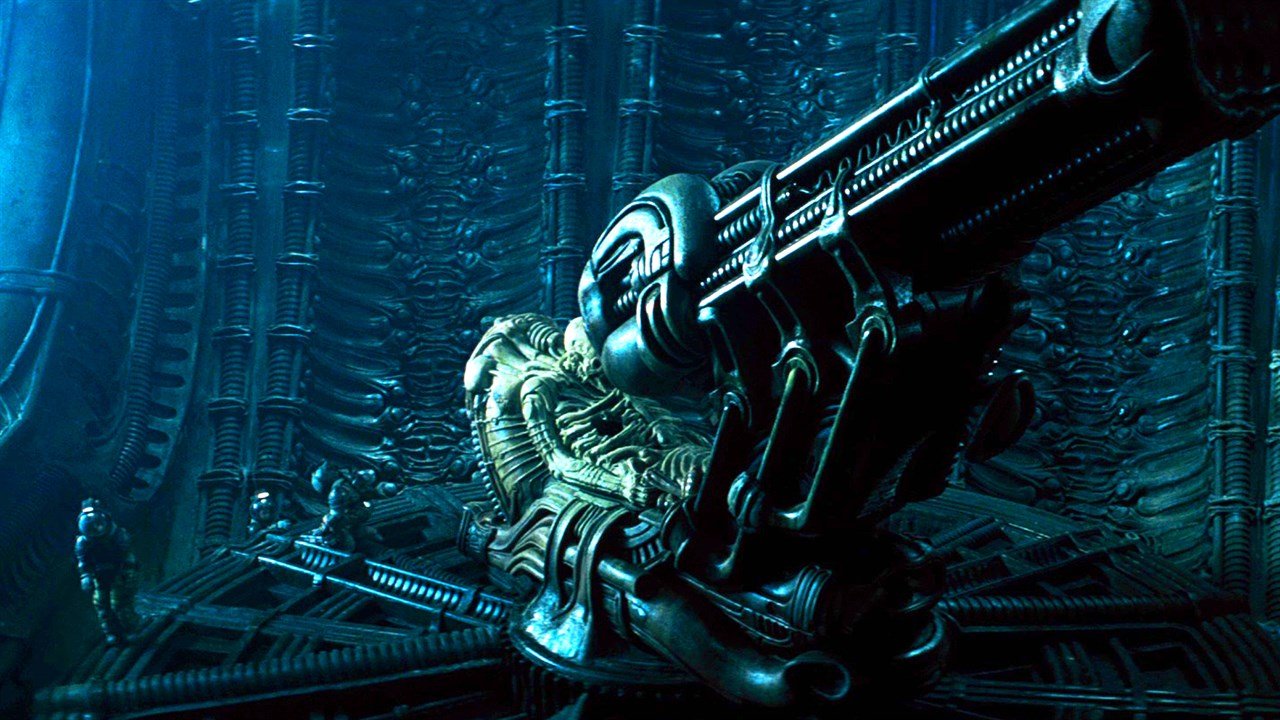

The ship also looks like a real, working object - the room with the chains and the dripping water, the cool iris hatches in the corridors. And outside, space looks fantastic - distant galaxies and colourful planets.

The story is now the stuff of legend - the Nostromo’s computer, “Mother”, has pulled the crew from suspended animation in order to investigate a distress call. The crew take a shuttle down to a nearby planet where there’s a big alien ship apparently crash-landed (well, the weather is terrible). They decide to explore the ship, leaving scientist Ash (Ian “Bilbo” Holm) and second-in-command Ripley (Sigourney “surely that’s not a real name?” Weaver) fixing the shuttle. For the modern viewer, Ash's clowning around as the others set off to check out the alien ship looks far more sinister when you know what he's up to - as is his reaction to Ripley's deciphering of the message as a warning, not a distress call: "By the time it takes (us) to get there, they'll know if it's a warning or not..."

Another thing that becomes apparent is that John Hurt's character Kane (yes, that John Hurt - the camp guy who played Alan Clarke and The Naked Civil Servant) is being made out to be the hero of the film, in a conceit similar to the structure of Psycho. He’s the first to volunteer for the mission, and the bloke who goes into the hole. He's also pretty stupid - I mean, would you poke at a huge "leathery egg" if there was something moving around inside it? But poke it he does, and it’s not too long before the thing inside has burst out, melted through the inch-thick glass of his space helmet, and attached itself to his face.

Back on the shuttle, after Ash has disobeyed Ripley’s orders and allowed the “contaminated” Kane back on board, they set about trying to remove the parasite from his face, and fail miserably – as a defence mechanism, having acid for blood is on the impressive side (and gives rise to the second most memorable scene in the film, when the group travel down and down through the decks, watching the “blood” eat through the floors).

Then this vicious, fast-moving, acid-spitting alien menace disappears. So what do they do? In the time-honoured tradition of all horror films, they wander into the room where it was last seen, armed to the teeth with flimsy plastic sticks with lights on the end. Luckily, the plastic sticks with lights on the end aren’t needed, as the creature is already dead, and the crew is soon sitting down to a celebration meal, which is wrecked when Hurt forgets his table manners and explodes all over everyone, “giving birth” to his own little comedy glove puppet. Of course, after that it's out with the cattle prods and the home-made alien detectors (which unfortunately also pick up cats), and the wholesale slaughter of the crew begins.

Secret robot Ash's "death", peculiarly, is the most disturbing - considering there's no blood. As is his attempt to kill Ripley by shoving a rolled-up jazz mag down her throat. Ripley (who has already proved herself to be the real hero of the film several times already) then decides to blow up the ship. Then tries to save it. Here’s a point worth thinking about for any spaceship builders who might be reading this in the future - what's the point of a five minute warning when it takes 30 seconds to stop the process? That only makes it a four-and-a-half minute warning…

But of course then we get the twist - that she's blown up that huge ship for no reason at all. The creature’s there, hidden in the tiny shuttle ship with her - but with the aid of some gratuitous lingerie shots, a broken strobe light and what appears to be a harpoon (wouldn’t that have come in handy early on? And why do they need a harpoon on a space ship?) Ripley finally manages to kill the creature. This alien is a lot tougher than anything that comes along in the later films. Not only does Ripley scald it, throw it into a vacuum and shoot it with an enormous harpoon, but it only actually dies when she fries it in the ship's rockets. In fact, I'm not convinced that even that does it. As a youngster I used to formulate ideas of the alien still being alive and drifting down onto another planet. A pretty small-scale idea for a sequel, as it turned out…

Alien is a great film - but is one of the few examples of a film being outclassed by its sequel in almost every way. Perhaps familiarity breeds contempt. But whatever way you look at it, it's been hugely influential - no sci-fi film has been the same since.